They’ve done it again. The vultures circling above Hollywood’s bloated corpse have found another scrap of flesh to pick at, this time yanking the still-warm remains of The Office off the shelf for a cynical, artless spin-off. This totally derivative show, The Paper, is so barren of purpose it might as well arrive with a coroner’s report stapled to the press kit. It is less an offspring of the original and more the embalming of a corpse that the studio still insists is breathing.

Oh, it’s awful. I couldn’t even get through the first episode. The original Office thrived on the chaos of personalities clashing and overlapping. What made it feel alive was the messy collision of egos, insecurities, and absurdities. The Paper gives us the opposite: a polite queue. Each character dutifully steps forward, delivers a flat line into the camera—too forced or too timid—and retreats. It isn’t comedy, it’s roll call.

The result feels like a high school yearbook project—fun for the kids involved, but pointless for the rest of us. They’ve checked the diversity boxes, but forgot the only box that matters: funny. What’s left feels like a Toyota-commercial script stretched out for a half hour; begging the viewer to acknowledge that it’s funny without actually being so. Even the hokey theme music, designed to pay homage to the original, serves more to remind us what we’re missing than of any shared DNA.

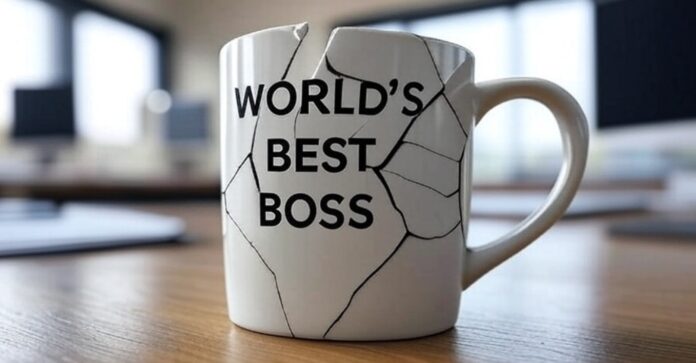

But there’s something here beyond godawful entertainment, something more nefarious, that deserves comment. This isn’t just bad television. There’s nothing new about that. It’s asset-stripping. It’s a business model straight out of Goodfellas: Pauly takes over a popular neighborhood restaurant that he did nothing to create, runs up bills on the joint’s hard-earned credit, bleeds it dry, and then sets the place on fire for the insurance money. Only here, the mobster is a corporate boardroom. The match is a marketing campaign. The payout is one last surge of nostalgic viewership before the brand collapses into a pile of licensed Funko Pops and ironic coffee mugs.

It’s the same playbook private equity uses when it takes over a struggling company. They don’t buy it to make it better, they buy it to squeeze out the last molecules of profit before the carcass collapses. Strip the assets. Collect the subscription fees and accounts receivable. Fire the people who know what they’re doing. Load it with debt until it groans. Then walk away from the smoldering ruin, pockets full. Sears. Kmart. Payless Shoes. Hostess. Toys “R” Us. Different industries, same scavenger’s instinct: get in, grab what you can, and leave the shell for someone else to bury.

The new Office is precisely that kind of vulture investment. It offers nothing new—no fresh perspective, no inventive comedy, no reason to exist beyond wringing the last molecules of nostalgia out of a once-great property. In place of heart, it has branding. In place of humor, it has callbacks. In place of character, it has trademarks.

This cultural vandalism has become so commonplace, it’s now an accepted business model. The Lord of the Rings was gutted for a streaming series that looked like a mid-tier video-game cutscene, stripped of the depth that made Tolkien timeless. Indiana Jones was dragged out of the nursing home for one last joyless shamble. And let’s not forget Disney, perhaps the worst of the offenders, having churned Star Wars into such oblivion that even lightsabers—once the most thrilling toy of childhood imagination—now feel boring. Lightsabers! And that’s just the beginning with those guys! Disney—or rather the corporate suits who inherited the once-great brand Walt built before they were even born—have turned the company’s entire vault into a recycling plant, endlessly remaking and “reimagining” its own classics, living parasitically off nostalgia while poisoning the present. The corporate logic never changes: why risk creating something new when you can keep milking the carcass of what’s already familiar?

And here’s the cruel irony—they will get away with it, at least for a while, because enough of us will rubberneck. We’ll tune in out of morbid curiosity, hoping against hope that the magic might somehow return. It won’t. What you’ll get instead is corporate taxidermy: the same familiar skin stretched over a hollow frame, posed in a grotesque imitation of life.

Even if the vultures weren’t circling, even if the accountants weren’t running the show, Hollywood would still be incapable of producing anything worth watching, because the creative process itself has become more over-regulated than New York City’s building code. Think of a brilliant architect sketching a soaring, visionary design—only to see it dismantled in a gauntlet of zoning boards, environmental studies, affordability panels, historical preservationists, neighborhood activists, and labor unions each taking a bite. By the time everyone has “had their say,” the design has been shaved down into a beige box that excites no one, offends no one, and inspires no one.

That’s how movies and TV shows are made now. Before a single line is written, the rules are already in place. It must not offend anyone, anywhere. It must include everyone, everywhere, whether the story calls for it or not. So rather than create content that’s relatable and imaginative, Hollywood just strip-mines the past, or (and I don’t know what’s worse) makes braindead comic-book movies, where they can conjure up an infinitely customizable cast that ticks every box and glides through a dozen layers of corporate sensitivity review without friction.

Oh, and just in case they haven’t alienated the audience quite yet, they’ll sprinkle in a left-leaning political message for you as well, usually with all the subtlety of a jackhammer. Because nothing says “creativity” like art assembled by algorithm, actuary, and activism.

Let’s be clear: the problem isn’t representation itself — done organically, it strengthens a story. But when it’s a corporate checklist, a cheap substitute for substance, characters flatten into archetypes and stories collapse into brochures with soundtracks.

Apply these rules to short-form television — especially comedy — and the whole thing collapses. Comedy works precisely because it’s supposed to challenge the rules, because it isn’t supposed to be safe. It’s where someone else says for us what we can’t say, where characters behave the way we might secretly want to but can’t for fear of real-world consequences, where we ridicule without fear, and even laugh at ourselves. Why was The Office funny? Because we’ve all worked with those people — the idiot boss, the office flirt, the neurotic, the slacker, the insufferable suck-up — and lived the stresses and unfair treatment and politics. It’s a comedy goldmine! But shutter the mine with edicts about what can’t be said or done, and all that remains is a ghost town. It’s like taking the NFL and turning it into flag football, but without the running (too dangerous) and the scoring (too offensive). I wouldn’t watch that, so why should I watch this?

Steve Carell has said The Office “might be impossible to do today,” because its cringe-driven satire, built on Michael Scott’s inappropriate behavior, wouldn’t “fly” in our heightened climate of sensitivity. But why would it not considering the enduring popularity of the original? If anything, that so many of us watch the repeats beyond the point of memorization demonstrates a ready-made audience hungry to challenge the status quo, if given the chance. It’s only if you’re determined to take away the edge, play by the new rules, make no real effort, grab the easy money, that Carell is proven right, because all you’re left with then is a sterile, robotic echo of something that once fought to be funny, and ended up just lifeless.

And so we’re trapped. We can’t create anything new for fear of alienating someone. We can’t revisit the old without sanding off all the edges that made it great. So what remains is the worst of both worlds: the leveraged buyout of our cultural memory, carried out by committees who wouldn’t know originality if it fell from the ceiling and landed in their soy lattes, and don’t really care to because easy money is easy.

The new Office isn’t a reboot. It’s not a reimagining. If anything, it demonstrates a total lack of imagination. It’s a corporate fire sale on the past, a calculated act of cultural arson disguised as a warm invitation to return. It’s what happens when the people in charge of entertainment no longer see themselves as storytellers but as asset managers, and when the only stories they’re willing to tell are the ones that have already been told — stripped for parts, repackaged, and sold back to you at a markup. Watching it is like visiting the ruins of a city you loved, only to find a strip mall in its place.

You can watch it, of course. Many will. Just like many watched Babe Ruth playing for the Braves, and Michael Jordan playing for the Wizards, and Mike Tyson boxing Jake Paul. Morbid curiosity and a longing for past greatness combine for a powerful, though often ephemeral allure. But know what you’re seeing. You’re not watching the next chapter of The Office. You’re watching the insurance fire Pauly’s men lit in the restaurant, except this time, you’re the insurance payout.

You may also be interested in: