The Democrats’ approach to the issue of illegal immigrants receiving free health care is a perfect case study in what can only be described as a trilateral contradiction. It’s a rhetorical pretzel that twists itself into three incompatible shapes at once—each one canceling out the others, yet all delivered with the same tone of moral certainty.

The first claim is categorical denial: It’s not happening. The second is reluctant concession: It’s happening, but it’s Reagan’s fault. The third is moral justification: It’s happening, and it should happen.

Three positions. One issue. No consistency.

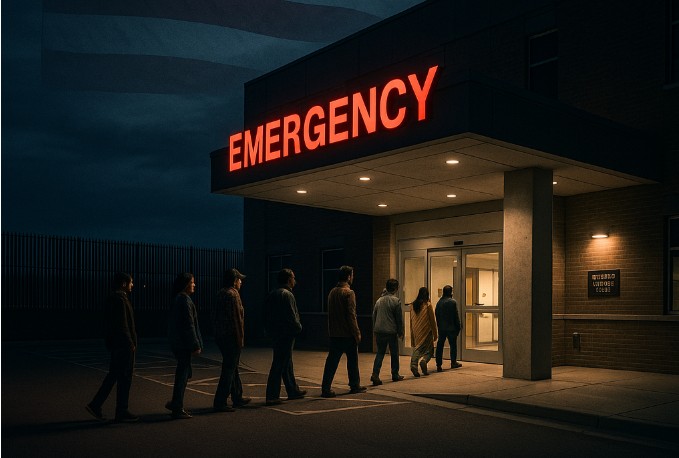

You can watch this play out almost word-for-word whenever the subject of illegal immigration and health care surfaces. Democrats and their media allies will begin by insisting that illegal immigrants are not getting free health care, as if the claim were a right-wing conspiracy. When pressed, they pivot to the legal fallback—that hospitals are required under a Reagan-era law, the 1986 Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA), to provide emergency care to anyone who walks in the door, regardless of immigration status. And finally, when the moral framing becomes unavoidable, they make the emotional appeal: that it would be cruel or “un-American” to deny care to someone in need.

This three-pronged sequence—the denial, the deflection, and the defense—amounts to the political equivalent of saying: My client wasn’t even there. But if he was there, he didn’t rob anybody. And if he did rob somebody, he didn’t use a weapon. And if he did use a weapon, he only did it in self-defense.

It’s a tactic I’ve seen countless times in court, usually from desperate attorneys who have run out of credible options. It’s what happens when a lawyer stops believing his own case and starts throwing arguments like darts, hoping one will stick. Each argument may sound plausible on its own, but together they destroy the very thing a jury—or a voter—needs most: a consistent theory of truth.

Politics, like law, depends on credibility. Once you’ve contradicted yourself three times in one breath, you’ve lost it.

The problem with the trilateral contradiction isn’t just that it’s dishonest—it’s that it’s lazy. It reveals a mindset that would rather manage appearances than grapple with reality. Democrats could, if they wished, make a single, coherent argument about illegal immigrants and health care: that compassion requires us to treat people in need, regardless of legal status. That would at least be a morally defensible position, even if unpopular. But they don’t. Instead, they attempt to hold every position at once: deny the problem, blame someone else, and demand virtue points for it.

The result is political incoherence disguised as compassion.

And it’s not limited to health care. The trilateral contradiction is fast becoming a defining feature of modern progressive rhetoric. On crime, they say: There’s no crime wave—but if there is, it’s because of poverty—and besides, prisons don’t solve anything. On inflation: It’s not happening—but if it is, it’s actually a sign of a strong economy—and anyway, corporations are to blame. On border policy: The border is secure—but if it’s not, it’s Trump’s fault—and besides, these people deserve asylum. Or how about the Obama Administration’s official positions on the border: bad people are not coming across, we only deport bad people, we’ve deported 3 million people, the border is secure.

Each of these tripartite defenses (the last is arguable a quadrangular) serves the same purpose: to appear both factual, moral, and innocent, all at once, without having to commit to any of the three. It’s a way of having every argument without having a position.

This is why people don’t trust politics anymore. When you say everything, you’re really saying nothing.

Contrast that with how an honest advocate argues. A good attorney, one who respects both the court and the truth, presents a single, unified theory of the case. It might not explain everything perfectly, but it hangs together. It acknowledges weaknesses, confronts facts head-on, and offers the jury a reason to believe. The bad attorney, by contrast, hurls out five different stories and dares the jury to pick one. That’s not persuasion; that’s confusion.

And confusion, in politics, is power. If you can keep people from knowing what’s true, you can make them believe whatever serves you in the moment.

That’s why the trilateral contradiction matters. It’s not just a communication flaw; it’s a moral one. It represents a deeper decay in how our leaders think about honesty and accountability. To them, truth isn’t a destination—it’s an obstacle. The goal isn’t coherence but control.

Now, to be fair, a good moral case can be made for compassionate care. No reasonable person wants emergency room doctors checking a patient’s passport before treating a gunshot wound or a heart attack. We are not a nation that leaves people to die in parking lots. There is a moral duty, both civic and Christian, to help the suffering. But that raises a deeper question: what qualifies as an “emergency”? When anyone who prefers the ER to a primary care visit can claim that status, “emergency” becomes a loophole large enough to drive an ambulance through. What began as an act of mercy becomes, over time, an unbounded entitlement.

And here we encounter a second contradiction, one shared by both sides. The Christian thing to do, plainly, is to help the sick and needy, regardless of nationality. Yet many on the Christian Right forget that when the subject turns to immigration or public health. Meanwhile, the secular Left demands that we affirm unlimited compassion, while simultaneously condemning any hint of Christian moral influence in public policy. The same people who lecture the nation on what Jesus would do also insist that Jesus has no place in the conversation.

So we end up with a strange moral inversion: Christians ashamed to apply their own faith, and secularists happy to weaponize it when convenient. That’s not compassion. That’s performance.

The trilateral contradiction, in the end, is not just a political problem but a moral one. It reflects a culture that has lost the courage to be consistent—whether in faith, policy, or plain reasoning. The truth is not complicated: a society can be both compassionate and lawful, merciful and just. It only requires honesty about what each of those words actually means.

But honesty is the one argument neither party seems eager to make.

You may also be interested in: