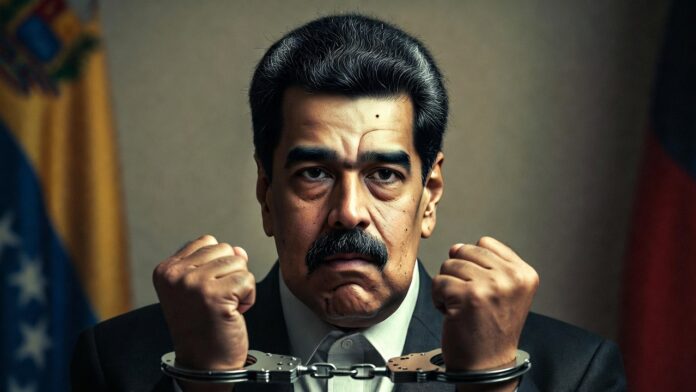

The reaction to the arrest of Nicolás Maduro has followed a familiar script. Words like sovereignty, regime change, and imperial overreach are invoked with ritualistic certainty, often detached from the facts on the ground. Beneath these objections lies a deeper discomfort with the reassertion of American hegemony, not in the sense of territorial conquest or permanent domination, but as the exercise of preponderant influence sufficient to deter criminal states, enforce international norms, and shape the behavior of other nations without occupying them. Whether such hegemony is desirable is a fair question; whether it exists, or whether its absence leaves a vacuum filled by less restrained powers, is the question this episode forces back into view. What is ultimately at issue, then, is not merely the propriety of a single operation, but the meaning of sovereignty itself, the conditions under which it is forfeited, and the strategic posture of the United States in a changing world.

Much has been made of the U.S. violating Venezuelan sovereignty, but nothing about Venezuela violating our own. To be clear, every time drugs enter our country it is a violation of our sovereignty, and an attack on our democracy. That Venezuela is not a major producer of fentanyl, a point frequently raised, is almost entirely irrelevant. Cocaine remains a profoundly destructive drug, and Venezuela has functioned as a narco-state and transit hub facilitating the flow of cocaine into the United States, fueling gang violence, organized crime, and social collapse in American cities. Entire communities, often minority communities, have paid the price. We have allowed our country to be attacked and poisoned for far too long, and the insistence that the heretofore failed “War on Drugs” must remain confined within our borders has become a convenient fiction. If criminal enterprises are international, then enforcement cannot remain purely domestic. Externalizing an external problem is not escalation, it is realism.

When a regime actively facilitates transnational crime, it forfeits the moral shield of absolute sovereignty. Harboring criminals who violate our laws, and doing so as a matter of state policy, is itself a violation of sovereignty. The idea that sovereignty is a one-way obligation, binding on law-abiding states but immunizing criminal ones, is neither coherent nor sustainable.

And no, this is not “regime change.” If anyone is guilty of that, it is the Maduro government that ignored the democratic vote of the people, and changed it to their own liking to stay in power. No serious person argues that Maduro was legitimately elected. International observers, opposition leaders, and even former allies have rejected the credibility of Venezuela’s electoral process. All the United States is doing (I hope) is liberating Venezuela from a criminal dictatorship, and supporting the government that the people of Venezuela chose.

Elections stripped of competition, transparency, and consequence are not elections in any meaningful sense. Sovereignty does not attach to criminal control masquerading as government. It flows from legitimate authority, exercised on behalf of a people, through institutions that constrain power.

This is why comparisons to Iraq fail. Venezuela is not a blank slate upon which democracy must be imposed. Until relatively recently, it possessed real democratic institutions and a functioning civil society. Those institutions were not overthrown by tanks; they were hollowed out from within, first through elections (yes, Venezuelans elected Hugo Chávez), then through systematic repression, fraud, and cartelization of the state. Democracy can fail from within when institutions are weak and voters repeatedly reward leaders who vilify private enterprise and promise centralized economic control. But the key distinction remains: a political structure and democratic tradition already exist, however damaged they may now be.

Nor are we at war with Venezuela. The target is not the Venezuelan people, the Venezuelan nation, or Venezuelan territory. The target is an illegitimate criminal government. That matters for both law and legitimacy. Law enforcement actions against transnational criminal leadership do not become acts of war simply because the criminals have wrapped themselves in flags.

Still, the real judgment will not be rendered in a single night. The fortune, as ever, is in the follow-up. What happened will be measured by what unfolds over the coming weeks, months, years, and even decades. The operation itself appears to have achieved its immediate objective with precision. But setbacks are inevitable. How those setbacks are handled—legally, diplomatically, and strategically—will determine whether this moment is remembered as a turning point or a missed opportunity.

Questions about legal authority inevitably follow. Whether Congress needed to authorize this action explicitly is a serious matter, though not an unprecedented one. If one had to speculate, it is likely that existing narco-terrorism authorities and broadly worded post–9/11 congressional authorizations were relied upon, much as prior administrations did under the War on Terror. The clue is in the consistent use of the term “narco terrorist” by the Trump Administration. So while no statute explicitly authorizes action against Maduro by name, modern executive power has long rested on general grants of authority triggered by vaguely defined threats.

There is also a broader strategic dimension that cannot be ignored. Ideally, this action will produce more deterrent value than diplomatic cost. Other regimes must be reminded that facilitating crime against the United States carries consequences, and others still that it’s better to be our friend than our enemy. This is not only about drugs or oil, though both factor in. It is about weakening the not-so-informal axis that has emerged among China, Russia, Iran, and Venezuela, an alignment driven less by ideology than by shared hostility to American influence and Western legal norms. Venezuela has long been the weakest leg of that arrangement. Removing it matters.

This, in turn, reflects a deeper feature of contemporary American strategy. Trumpism begins from the premise that global power is consolidating to challenge and threaten us, while the United States has spent decades receding. From this perspective, actions that add to the American empire, especially in our own hemisphere, are not indulgences but necessities. Hence, Trump’s prior overtures to acquiring Canada and Greenland, both of which we’ve correctly criticized. This, though, is not an acquisition of territory, but rather of a new ally at the expense of our enemies. The Ukraine-Russia War is tricky because Russia is a nuclear power with a modern military and Europe doesn’t want to lift a finger. But Venezuela is in our backyard bound to us by geography, history, and economic gravity. Flipping a hostile state into a friendly one is seen not as adventurism, but as strategic acquisition, and it may prove to be the correct one.

And while we cannot know for certain, at least for some time, something more than incidental is already observable which may be instructive: that the loudest complaints about this action have come not from Venezuelans, but from Western commentators speaking “on behalf of” them. Venezuelan-Americans, particularly those who fled the regime, are openly supportive of our actions. That disconnect should give pause to anyone confident they are defending the oppressed rather than projecting abstractions.