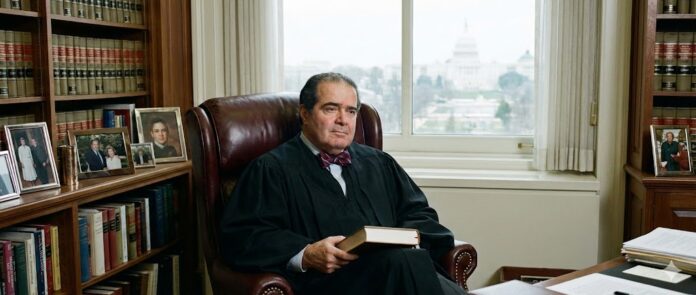

When I was in law school, Antonin Scalia was idolized by the few conservatives who were there, myself included. His opinions were quoted, his dissents memorized, his rhetorical flourishes admired even by classmates on the Left who rarely agreed with him but could not deny his panache. Law students, as a rule, enjoy pretending that the great legal minds of the past do not quite measure up to us. That pretense rarely survived contact with Scalia. He was, by any honest measure, a towering jurist and a great American.

And yet, with the benefit of time and experience, I have come to wonder whether his stubborn adherence to originalism — the idea that laws should be interpreted strictly according to their original public meaning — may have been, in at least one important respect, incomplete.

Originalism has done the conservative legal movement an enormous service. It restored respect for text. It reminded judges that the Constitution is law, not poetry. It rejected the conceit that unelected jurists are licensed to improve the work of those chosen by the people. These are not small achievements, and conservatives are right to defend them.

And no jurist did more to restore seriousness to constitutional interpretation than Scalia. At a moment when the Constitution was increasingly treated as a canvas for judicial aspiration, Scalia insisted that it was law. He demanded fidelity to text, skepticism of judicial creativity, and an honest confrontation with history. Those demands were not reactionary. They were corrective. American conservatism owes him a debt for forcing courts to remember that they govern only by permission, not wisdom.

But Scalia’s success also hardened originalism into something more than a method. In its most rigid form, it became an article of faith: that the original public meaning of a law is not merely the starting point of interpretation, but the ending point as well. That move, however well-intentioned, risks mistaking interpretive discipline for interpretive completeness.

The problem with an originalist-only approach is that law does not exist only at the moment of its enactment. It exists because it continues to exist.

A statute passed by Congress does not remain law because its authors once voted for it. It remains law because every Congress since has affirmed it by declining to repeal it, and by not repealing it, it has reaffirmed it in its own time. That fact is not incidental. It is the central feature of democratic legitimacy. Congress sits continuously. It revisits, revises, repeals, and replaces laws all the time. A law that survives decades or centuries does so not by accident, but by sustained political tolerance, exercised by legislators fully aware of the world in which they govern.

That matters for interpretation.

If a law’s authority derives in part from its continued survival through repeal-capable legislatures, then its meaning cannot be confined entirely to the mental furniture of those who first enacted it. The people who wrote the law gave it life. But the people who maintained it gave it endurance. Both count.

Originalism, when practiced honestly, recognizes this at least implicitly. No serious originalist believes that the First Amendment protects only quill pens, or that the Fourth Amendment evaporates in the presence of digital data. We do not ask whether the Founders anticipated smartphones before applying constitutional protections to them. We ask whether modern circumstances fall within the principles the Constitution established.

That is not a betrayal of original meaning. It is the only way original meaning can survive contact with reality. If democratic continuity means anything, it must mean something where the distance between founding context and modern reality is greatest.

Nowhere is this clearer than with the Second Amendment. When it was ratified, the most advanced personal weapons were muskets. By the time the Fourteenth Amendment extended the Bill of Rights against the states, firearms had evolved considerably. Today, they have evolved further still.

Yet we conservatives rightly insist that the Second Amendment not be treated as a historical curiosity, but as a continuing guarantee of the right to bear arms — not antique arms, but arms.

This is not because courts have invented a new right. It is because the American people, through centuries of political continuity, have reaffirmed the principle the Amendment protects. To pretend otherwise is to suggest that the right endures while its substance evaporates. That is not fidelity to the Constitution. It is formalism masquerading as restraint.

The same is true of the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment. What qualifies as “cruel and unusual” has never been fixed. Practices once accepted are now rejected. That evolution did not occur because judges became more enlightened than the people. It occurred because the people themselves changed their standards, and the law followed.

This is not judicial activism. It is judicial recognition of moral reality.

The Constitution is written in broad terms precisely because it was designed to endure. It speaks in principles, not inventories. Those principles must be applied by human beings exercising judgment in circumstances the Framers could not fully imagine. To deny that judgment plays a role is not to eliminate discretion. It is merely to conceal it.

Some originalists resist this conclusion because they fear it licenses courts to invent rights. That fear is justified. Courts have invented rights, and the damage has been substantial. But acknowledging the role of judgment does not require surrendering to invention.

There is a critical distinction between applying an existing right to new circumstances and conjuring a right that was never enacted, debated, or ratified. The former is unavoidable. The latter is illegitimate.

This is where the modern Left reveals its inconsistency. It demands rigid originalism when interpreting rights it dislikes, such as the Second Amendment, insisting that modern application must be limited by eighteenth-century technology. Yet it abandons originalism entirely when defending rights like abortion, which have no grounding in constitutional text, history, or structure.

Conservatives should not accept this false choice. We need not choose between freezing the Constitution in 1791 and rewriting it in 2026. There is a middle ground, and it is the ground on which the Constitution has always operated: textual fidelity informed by historical understanding, applied through reasoned judgment, and constrained by democratic continuity.

Rules matter. They restrain power. But rules cannot eliminate the need for judgment, and pretending otherwise does not make law more objective. It merely makes it more brittle.

The conservative commitment is not to mechanical interpretation, but to ordered liberty. That requires discipline, humility, and an honest acknowledgment that time does work on law, not by erasing its meaning, but by testing and shaping it.

It is one thing to defend originalism as an interpretive tool. It is another to treat it as the only legitimate source of constitutional meaning. A jurisprudence that refuses to account for democratic continuity does not eliminate judgment; it merely pretends judgment is unnecessary.

Originalism reminds us where the Constitution came from. Democratic reaffirmation reminds us why it still governs. A jurisprudence worthy of a living republic must take both seriously.